Lost in Translation: The Quiet Death of Japan's Local Dialects

Mongolian-Throat-Singing Table-Tennis-Dancing and the Disappearing Dialects of Japan

Yamagata cops a lot of flack for its dialects.

And for good reason.

When people ask if I can understand the local Shonai dialect, I tell them: my wife doesn’t even understand it.

And she’s a born-and-bred Yamagatan.

Okay, that’s a little disingenuous. She understands Shonai dialect just fine, just not the version her grandmother spoke.

Whatever that was.

True story: like we might need subtitles to understand Mickey the Irish Traveller boxer from Snatch, my wife needed her mum to translate what her grandmother was saying. And people expect me to understand that?

We’re talking just two generations. That’s how fast dialects can disappear. A once-thriving way of speaking turns into something barely recognisable, even for locals.

People assume dialects are quirky ways of speaking. Slang. Funny accents. Strange grammar.

But they’re much more than that.

Dialects carry history. They’re shaped by the land people live in, the food they eat, the work they do, and the values they hold.

Take The Shonai Region of Yamagata, for example.

For most of its history, Shonai was like an island, just not the kind surrounded by water.

To the north we have the glorious Chokai-san (Mt. Chokai), with cliffs dropping into the Sea of Japan. To the east, the towering Asahi and Iide ranges, cutting Shonai off from inland Yamagata. To the south, the so-called Shonai Alps (how’s that for dialect?), another mountain barrier. And to the west: The Sea of Japan. A barrier if there ever was one.

And then there’s the winter.

“Winter is coming” hits different in Shonai.

This is Yukiguni. Japan’s snow country. What that cocktail from last time was named after. Here villages are buried under the white stuff for months. The only way in or out? Make like Tom Cruise in The Last Samurai and…

wait for the snow to thaw.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom, though. This isolation did something interesting:

It created a dialect or two.

Or five.

Then starting in the 17th century, Kitamaebune trade ships brought the outside world in. They sailed from Edo (Tokyo) to Osaka to Fukuoka to Sakata to Hokkaido and back, bringing goods, ideas, and most importantly,

words.

Dialect, if you will.

Sakata, Shonai’s port, absorbed these influences, especially from Kyoto, the cultural capital of the time. That’s why there’s still a thriving Maiko and Geiko culture way up here.

But go a town or so over and the dialect shifts again. Sometimes to the point of near incomprehensibility.

Sure, we have that in English too.

Over continents, though.

In Japan? Sometimes it’s one town over.

That kind of dialect diversity barely exists in New Zealand. Sure, we Kiwis sound a little different. But honestly?

We all sound like that.

Okay, maybe not Soimun Brudges. And Southlanders still roll their ‘r’s thanks to Scottish settlers (called rhoticity, the biggest factor determining types of English).

But that’s about it.

Shonai, though? Shonai has layers upon layers of dialects.

Thankfully, there’s enough left for some rudimentary Shonai dialect I can manage.

And I’m willing to bet you can too:

Repeat after me:

け = Ke.

く = Ku.

こ = Ko.

You just said: “Eat up,” “I will eat up,” and “Let’s eat up!” in Shonai Dialect.

Three words about eating. All one syllable. Snow country efficiency at its best.

Because, as we know,

Japan is all about efficiency:

パソコン (Pasokon) = Personal Computer. PC.

コンビニ (Konbini) = Convenience Store.

And my personal favourite:

ブレスト (Buresuto) = Breast. Oh, wait, sorry… this one is short for Brainstorming (true story).

Or just watch the master at work: Katsura Sunshine:

Which begs the question:

Why are the dialects disappearing?

One word: Standardization.

During the Meiji era (1868–1912), Japan pushed hard for linguistic unity. Standard Japanese became the language of school, business, and media.

At the time, it made sense. A modern nation needed a common language.

But now? That push for uniformity is backfiring.

Kids grow up speaking only Standard Japanese. Dialects get labeled “uncool” or “unprofessional.” Even local media favours Tokyo-style speech.

The result?

A rich, diverse linguistic landscape gets flattened.

And what do we lose?

We lose place.

A Tokyo kid and a Shonai kid end up speaking the same way, even though their lives couldn’t be more different.

We lose humour.

Many dialects have their own comic timing, punchlines, and rhythm. Ever notice how many Japanese comedians come from Kansai, home of Osaka-ben? That’s no accident.

We lose belonging.

Dialects are social glue. They signal where you’re from and who you’re with. Without them, regional identity fades.

People stop speaking their dialects. Worse, they apologize for them.

Case in point:

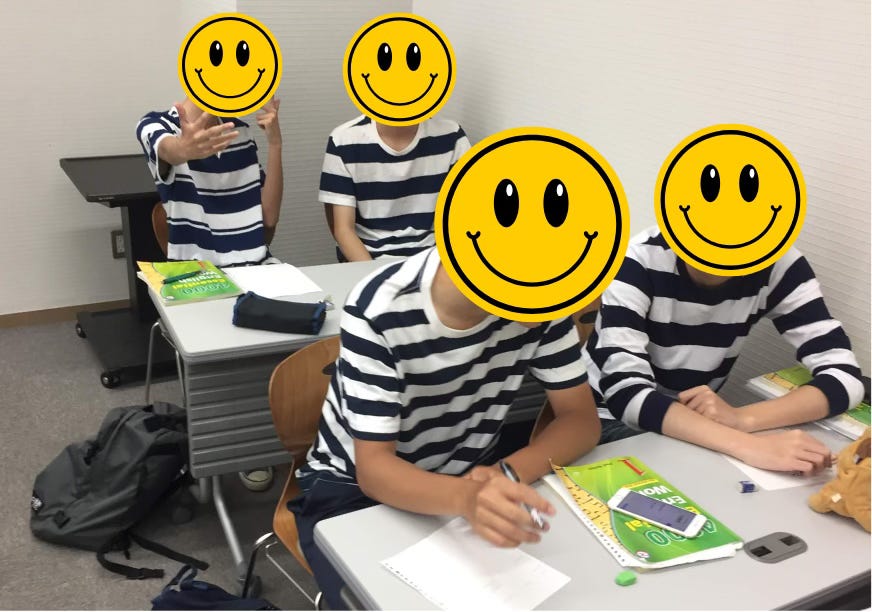

I was crammed behind a desk designed for someone half my size, balancing my school lunch so well it didn’t fall off,

still one of my proudest moments.

The kids were already shell-shocked that a foreigner was sitting with them. I’m pretty sure one of them-Takayuki, I see you—is still wondering whether I was telling the truth about my blue eyes being able to see his farts1.

And then came the voice.

You know the one. If you’ve ever been in a Japanese school, watched Squid Game, or played Resident Evil, you know it.

The loudspeaker voice.

“Kyō no danshi takyūbu no renshū wa chūshi ni narimashita.”

“Today’s boys’ table tennis has been cancelled.”

Except that’s not what I heard.

Instead of danshi (boys), they said dansu.

Dance.

“Today’s dance table tennis practice has been cancelled.”

Dance table tennis!

Are we talking dance table tennis and techno music? Because that’s something I could get behind.

Mongolian throat singing, though?

Imagine dance-table-tennising to that!

You should be able to tell from context they meant boys’ table tennis. But I’m not from here. Maybe they did mean dance table tennis.

Or maybe it was a prank, like me telling kids I could see their farts.

Takayuki, I know that was you!

Or how about this:

Another time, at a hospital, a nurse asked an elderly man what he had for dinner.

His answer?

Sushi!

Except, instead of saying su and shi, to the untrained ear, it came out as su and su.

Susu. The Japanese word for:

Soot!

The old man had soot for dinner. Or so I thought.

When dialects disappear, even simple things like “what’s for dinner” become harder, or funnier, to understand.

But the real loss?

People stop feeling at home in their own language. Humour fades, belonging weakens, and the voices of places vanish.

That’s why we need to act before we’re all “eating soot for dinner.”

Use dialects. Speak them at home. Teach them to your kids. Don’t let them be something we only remember with a laugh or a cringe.

Celebrate them. Put them in books, on screens, on stage. Dialects aren’t mistakes to correct—they’re culture we can keep alive.

Because when we lose dialects, we lose far more than words. We lose a way of being.

Your next read:

Some related articles to this:

The Land of Salmon and Sake: How Sakata (Sake Rice Field) got its name

The Dragon Deity and Japan’s Number One Rice

The real star of Japanese cuisine

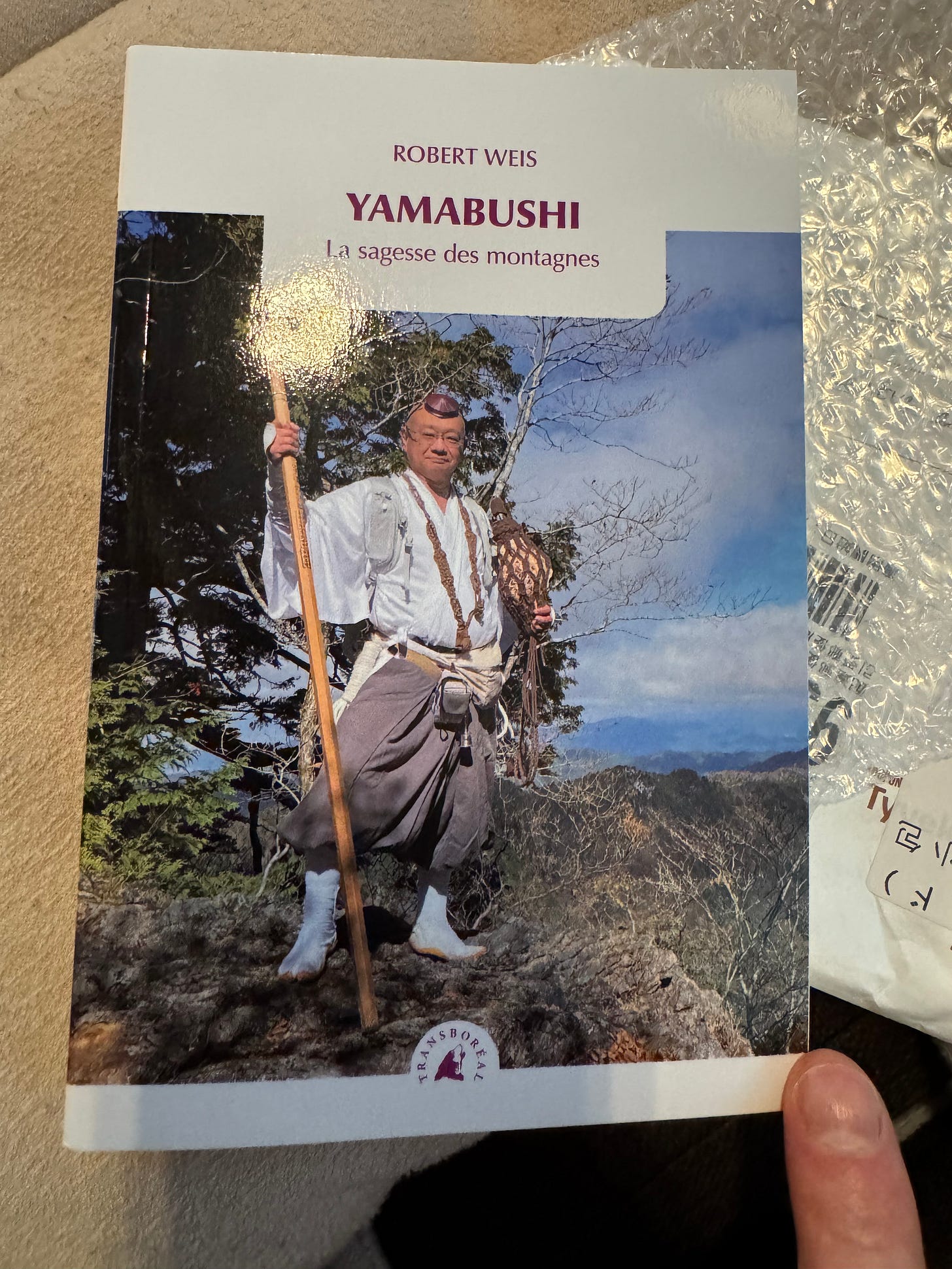

I’m in a book.

A French book (Oh là là)!

French speakers! If you missed it, my friend Robert Weis published a Yamabushi book late last year. Here’s an article on it and a link for you to purchase it :)

Daily Yamabushi for This Week

Daily Yamabushi posts for the week of March 21 to 27, 2025.

Read Daily Yamabushi at timbunting.com/blog. Everything I make is free of charge if you know where to find it. I’d start here.

A joke I stole from my friend.

My two favorite shortened words are

- pansuto for panty・stocking (panty hose)

- zensuto for zeneraru sutoraikki (general strike)

Very cool, I had no idea about Japanese dialects! Sad that they're vanishing. A similar thing the world over, of course. When I taught in Shanghai my Chinese students were generally working in their third language, English, after both Mandarin and their local dialect, or even entirely separate language--China has tons. Or did. The PRC has worked hard to push them aside, and demographics and tech do the rest. Anyhow. Great post, love seeing your students and the snow, too.

Do you know Minae Mizumura's book The Fall of Language in the Age of English? Great book about the same question on a national level. Your post made me think of it. I....read it in English, of course. You've probably already read it in the original Japanese!